"How now! good lack! what present have we here?

A Book that goes in peril of the press;

But now it's past those pikes, and doth appear

To keep the lookers-on from heaviness.

What stuff contains it?"

Davies of Hereford

| Main Index |

| Previous Part |

| CHAPTER XXXII | CATCHING SIGHT OF AN OLD FLAME |

| CHAPTER XXXIII | WOMAN'S A RIDDLE |

| CHAPTER XXXIV | THE RIDDLE BAFFLES ME! |

| CHAPTER XXXV | A MYSTERIOUS LETTER |

| CHAPTER XXXVI | THE RIDDLE SOLVED |

| CHAPTER XXXVII | THE FORLORN HOPE |

| CHAPTER XXXVIII | PACING THE ENEMY |

| CHAPTER XXXIX | THE COUNCIL OF WAR |

| CHAPTER XL | LAWLESS'S MATINÉE MUSICALE |

| CHAPTER XLI | HOW LAWLESS BECAME A LADY'S MAN |

| CHAPTER XLII | THE MEET AT EVERSLEY GORSE |

| CHAPTER XLIII | A CHARADE — NOT ALL ACTING |

| CHAPTER XLIV | CONFESSIONS |

| CHAPTER XLV | HELPING A LAME DOG OVER A STILE |

| CHAPTER XLVI | TEARS AND SMILES |

| CHAPTER XLVII | A CURE FOR THE HEARTACHE |

| CHAPTER XLVIII | PAYING OFF OLD SCORES |

| CHAPTER XLIX | MR. FRAMPTON MAKES A DISCOVERY |

| CHAPTER L | A RAY OF SUNSHINE |

| CHAPTER LI | FREDDY COLEMAN FALLS INTO DIFFICULTIES |

| CHAPTER LII | LAWLESS ASTONISHES MR. COLEMAN |

| CHAPTER LIII | A COMEDY OF ERRORS |

| CHAPTER LIV | MR. VERNOR MEETS HIS MATCH |

| CHAPTER LV | THE PURSUIT |

| CHAPTER LVI | RETRIBUTION |

| CHAPTER THE LAST | WOO'D AND MARRIED AND A' |

|

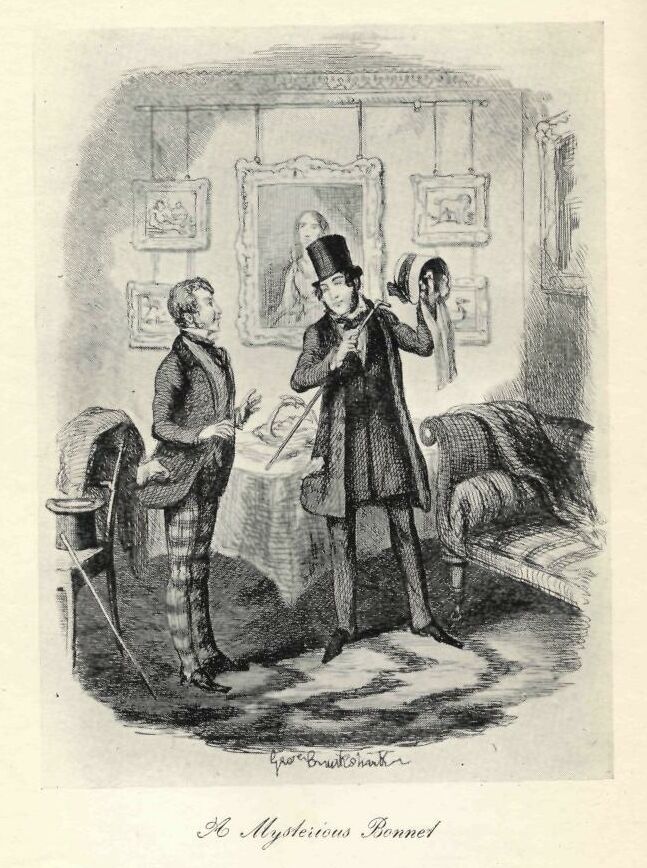

Page253 —— A Mysterious Bonnet Page266 —— An Unexpected Reverie Page345 —— A Charade Not All Acting Page382 —— A New Cure for the Heart-ache Page398 —— A Striking Position |

"Give me thy hand... I'm glad to find thee here."

The Lover's Melancholy.

"Half light, half shade,

She stood, a sight to make an old man young."

The Gardener's Daughter.

UTTERLY worn out, both in mind and body, by hard reading and confinement, I determined to return to Heathfield forthwith, with "all my blushing honours thick upon me," and enjoy a few weeks' idleness before again engaging in any active course of study which might be necessary to fit me for my future profession. When the post came in, however, I received a couple of letters which rather militated against my intention of an immediate return home. A note from Harry Oaklands informed me, that having some weeks ago been ordered to a milder air, he and Sir John had chosen Clifton, their decision being influenced by the fact of an old and valued friend of Sir John's residing there. He begged me to let him hear all the Cambridge news, and hoped I should join him as soon as Mrs. Fairlegh and my sister would consent to part with me. For himself, he said, he felt somewhat stronger, but still suffered much from the wound in his side. The second letter was from my mother, saying she had received an invitation from an old lady, a cousin of my father's, who resided in London, and, as she thought change of scene would do Fanny good, she had accepted it. She had been there already one week, and proposed returning at the end of the next, which she hoped would be soon enough to welcome me after the conclusion of my labours at the university.

Unable to make up my mind whether to remain where I was for a week longer, or to return and await my mother's arrival at the cottage, I threw on my cap and gown and [251] strolled out, the fresh air appearing quite a luxury to me after having been shut up so long. As I passed through the street where old Maurice the pastry-cook lived I thought I would call and learn how Lizzie was going on, as I knew Harry would be anxious for information on this point. On entering the shop I was most cordially received by the young lady herself, who had by this time quite recovered her good looks, and on the present occasion appeared unusually gay and animated, which was soon accounted for when her father, drawing me aside, informed me that she was going to be married to a highly respectable young baker, who had long ago fallen a victim to her charms, and on whom she had of late deigned to take pity; the severe lesson she had been taught having induced her to overlook his intense respectability, high moral excellence, and round, good-natured face—three strong disqualifications which had stood dreadfully in his way when striving to render himself agreeable to the romantic Fornarina. I was answering their inquiries after Oaklands, of whom they spoke in terms of the deepest gratitude, when a young fellow, wrapped up in a rough pea-jacket, bustled into the shop, and, without perceiving me, accosted Lizzie as follows:—

"Pray, young lady, can you inform me—what glorious buns!—where Mr.—that is to say, which of these funny old edifices may happen to be Trinity College?"

On receiving the desired information, he continued, "Much obliged. I really must trouble you for another bun. Made by your own fair hands, I presume? You see, I'm quite a stranger to this quaint old town of yours, where half the houses look like churches, and all the men like the parsons and clerks belonging to them, taking a walk in their canonicals, with four-cornered hats on their heads—abortive attempts to square the circle, I conclude. Wonderful things, very. But when I get to Trinity, how am I to find the man I want, one Mr. Frank Fairlegh?" Here I took the liberty of interrupting the speaker, whom I had long since recognised as Coleman—though what could have brought him to Cambridge I was at a loss to conceive—by coming behind him, and saying, in a gruff voice, "I am sorry you keep such low company, young man".

"And pray who may you be that are so ready with your 'young man,' I should like to know? I shall have to teach you something your tutors and dons seem to have forgotten, and that is, manners, fellow!" exclaimed Freddy, turning round with a face as red as a turkey-cock, [252] and not recognising me at first in my cap and gown; then looking at me steadily for a moment, he continued, "The very man himself, by all that's comical! This is the way you read for your degree, is it?" Then with a glance towards Lizzie Maurice, he sang:—

"'My only books

Were woman's looks,

And folly all they taught me'.

It's a Master of Hearts you're striving to become, I suppose?"

"Nonsense," replied I quickly, for I saw poor Lizzie coloured and looked uncomfortable; "we don't allow bad puns to be made at Cambridge."

"Then, faith, unless the genius loci inspires me with good ones," returned Freddy, as we left the shop together, "the sooner I'm out of it the better."

Ten minutes' conversation served to inform me that Freddy, having been down to Bury St. Edmund's on business, had stopped at Cambridge on his way back in order to find me out, and, if possible, induce me to accompany him home to Hillingford, and spend a few days there. This arrangement suited my case exactly, as it nearly filled up the space of time which must elapse before my mother's return, and I gladly accepted his invitation. In turn, I pressed him to remain a day or two with me, and see the lions of Cambridge; but it appeared that the mission on which he had been despatched was an important one, and would not brook delay; he must therefore return at once to report progress. As he could not stay with me, the most advisable thing seemed to be that I should go back with him. Returning, therefore, to my rooms, I set Freddy to work on some bread and cheese and ale, whilst I hastened to cram a portmanteau and carpet-bag with various indispensables. I then ran to the Hoop, and took an affectionate farewell of Mr. Frampton, making him promise to pay me a visit at Heathfield Cottage; and, in less than two hours from the time Coleman had first made his appearance, we were seated together on the roof of a stage-coach, and bowling along merrily towards Hillingford.

During our drive Coleman recounted to me his adventures in search of Cumberland on the day preceding the duel, and gave me a more minute description than I had yet heard of the disreputable nature of that individual's pursuits. From what Coleman could learn, Cumberland, after having lost at the gaming-table large sums of [253] money, of which he had by some means contrived to obtain possession, had become connected with a gambling-house not far from St. James's Street, and was supposed to be one of its proprietors. Just before Coleman left town, there had been an exposé of certain shameful proceedings which had taken place at this house—windows had been broken, and the police obliged to make a forcible entrance; but Cumberland had as yet contrived to keep his name from appearing, although it was known that he was concerned in the affair, and would be obliged to keep out of the way at present. "We shall take the old lady by surprise, I've a notion," said Freddy, as the coach set us down within ten minutes' walk of Elm Lodge. "I did not think I should have got the Bury St. Edmund's job over till to-morrow, and wrote her word not to expect me till she saw me; but she'll be glad enough to have somebody to enliven her, for the governor's in town, and Lucy Markham is gone to stay with one of her married sisters."

"I hope I shall not cause any inconvenience, or annoy your mother."

"Annoy my grandmother! and she was dead before I was born!" exclaimed Freddy disdainfully. "Why, bless your sensitive heart, nothing that I can do annoys my mother: if I chose to bring home a mad bull in fits, or half a dozen young elephants with the hooping-cough, she would not be annoyed." Thus assured, nothing remained for me but silent acquiescence, and in a few minutes we reached the house.

"Where's your mistress?" inquired Freddy of the man-servant who showed us into the drawing-room.

"Upstairs, sir, I believe; I'll send to let her know that you are arrived."

"Do so," replied Coleman, making a vigorous attack upon the fire.

"Why, Freddy, I thought you said your cousin was away from home?" inquired I.

"So she is; and what's more, she won't be back for a fortnight," was the answer.

"Here's a young lady's bonnet, however," said I.

"Nonsense," replied he; "it must be one of my mother's."

"Does Mrs. Coleman wear such spicy affairs as this?" said I, holding up for his inspection a most piquant little velvet bonnet lined with pink.

"By Jove, no!" was the reply; "a mysterious young lady! I say, Frank, this is interesting."

As he spoke the door flew open, and Mrs. Coleman [254] bustled in, in a great state of maternal affection, and fuss, and confusion, and agitation.

"Why, Freddy, my dear boy, I'm delighted to see you, only I wish you hadn't come just now;—and you too, Mr. Fairlegh—and such a small loin of mutton for dinner; but I'm so glad to see you—looking like a ghost, so pale and thin," she added, shaking me warmly by the hand; "but what I am to do about it, or to say to him when he comes back—only I'm not a prophet to guess things before they happen—and if I did I should always be wrong, so what use would that be, I should like to know?"

"Why, what's the row, eh, mother? the cat hasn't kittened, has she?" asked Freddy.

"No, my dear, no, it's not that; but, your father being in town, it has all come upon me so unexpectedly; poor thing! and she looking so pretty, too; oh, dear! when I said I was all alone, I never thought I shouldn't be; and so he left her here."

"And who may her be?" inquired Freddy, setting grammar at defiance, "the cat or the governor?"

"Why, my love, it's very unlucky—very awkward indeed; but one comfort is we're told it's all for the best when everything goes wrong—a very great comfort that is if one could only believe it; but poor Mr. Vernor, you see he was quite unhappy, I'm sure, he looked so cross, and no wonder, having to go up to London all in a hurry, and such a cold day too."

At the mention of this name my attention, which had been gradually dying a natural death, suddenly revived, and it was with a degree of impatience, which I could scarcely restrain, that I awaited the conclusion of Mrs. Coleman's rambling account. After a great deal of circumlocution, of which I will mercifully spare the reader the infliction, the following facts were elicited:—About an hour before our arrival, Mr. Vernor, accompanied by his ward, had called to see Mr. Coleman, and, finding he was from home, had asked for a few minutes' conversation with the lady of the house. His reason for so doing soon appeared; he had received letters requiring his immediate presence in London on business, which might probably detain him for a day or two; and not liking to leave Miss Saville quite alone, he had called with the intention of begging Mrs. Coleman to allow her niece, Lucy Markham, to stay with her friend at Barstone Priory till his return, and to save her from the horrors of solitude. This plan being rendered impracticable by reason of Lucy's absence.

[255] Mrs. Coleman proposed that Miss Saville should remain with her till Mr. Vernor's return, which, she added, would be conferring a benefit on her, as her husband and son being both from home, she was sadly dull without a companion. This plan having removed all difficulties, Mr. Vernor proceeded on his journey without further delay. Good Mrs. Coleman's agitation on our arrival bad been produced by the consciousness that Mr. Vernor would by no means approve of the addition of two dangerous young men to the party; however, Freddy consoled her by the ingenious sophism that it was much better for us to have arrived together than for him to have returned alone, as we should now neutralise each other's attractions; and, while the young lady's pleasure in our society would be doubled, she would be effectually guarded against falling in love with either of us, by reason of the impossibility of her overlooking the equal merits of what Mrs. Coleman would probably have termed "the survivor ". Having settled this knotty point to his own satisfaction, and perplexed his mother into the belief that our arrival was rather a fortunate circumstance than otherwise, Freddy despatched her to break the glorious tidings, as he called it, to the young lady, cautioning her to do so carefully, and by degrees, for that joy was very often quite as dangerous in its effects as sorrow.

Having closed the door after her, he relieved his feelings by a slight extempore hornpipe, and then slapping me on the back, exclaimed, "Here's a transcendent go! if this ain't taking the change out of old Vernor, I'm a Dutchman. Frank, you villain, you lucky dog, you've got it all your own way this time; not a chance for me; I may as well shut up shop at once, and buy myself a pair of pumps to dance in at your wedding."

"My dear fellow, how can you talk such utter nonsense?" returned I, trying to persuade myself that I was not pleased, but annoyed, at his insinuations.

"It's no nonsense, Master Frank, but, as I consider it, a very melancholy statement of facts. Why, even putting aside your 'antécédents,' as the French have it, the roasted wrist, the burnt ball-dress, and all the rest of it, look at your present advantages; here you are, just returned from the university, covered with academical honours, your cheeks paled by deep and abstruse study over the midnight lamp; your eyes flashing with unnatural lustre, indicative of an overwrought mind; a graceful languor softening the nervous energy of your manner, and imparting additional tenderness to the [256] fascination of your address; in fact, till you begin to get into condition again you are the very beau ideal of what the women consider interesting and romantic."

"Well done, Freddy," replied I, "we shall discover a hidden vein of poetry in you some of these fine days; but talking of condition leads me to ask what time your good mother intends us to dine?"

"There, now you have spoilt it all," was the rejoinder; "however, viewed abstractedly, and without reference to the romantic, it's not such a bad notion either. I'll ring and inquire."

He accordingly did so, and, finding we had not above half an hour to wait, he proposed that we should go to our dressing-rooms and adorn before we attempted to face "the enemy," as he rudely designated Miss Saville.

It was not without a feeling of trepidation, for which I should have been at a loss to account, that I ventured to turn the handle of the drawing-room door, where I expected to find the party assembled before dinner. Miss Saville, who was seated on a low chair by Mrs. Coleman's side, rose quietly on my entrance, and advanced a step or two to meet me, holding out her hand with the unembarrassed familiarity of an old acquaintance. The graceful ease of her manner at once restored my self-possession, and, taking her proffered hand, I expressed my pleasure at thus unexpectedly meeting her again.

"You might have come here a hundred times without finding me, although Mrs. Coleman is kind enough to invite me very often," she replied. "But I seldom leave home; Mr. Vernor always appears to dislike parting with me."

"I can easily conceive that," returned I; "nay, although, in common with your other friends, I am a sufferer by his monopoly, I can almost pardon him for yielding to so strong a temptation."

"I wish I could flatter myself that the very complimentary construction you put upon it were the true one," replied Miss Saville, blushing slightly; "but I am afraid I should be deceiving myself if I were to imagine my society were at all indispensable to my guardian. I believe if you were to question him on the subject you would learn that his system is based rather on the Turkish notion, that, in order to keep a woman out of mischief, you must shut her up."

"Really, Miss Saville," exclaimed Coleman, who had entered the room in time to overhear her speech, "I am shocked to find you comparing your respectable and [257] revered guardian to a heathen Turk, and Frank Fairlegh, instead of reproving you for it, aiding, abetting, encouraging, and, to speak figuratively, patting you on the back."

"I'm sure, Freddy," interrupted Mrs. Coleman, who had been aroused from one of her customary fits of absence by the last few words, "Mr. Fairlegh was doing nothing of the sort; he knows better than to think of such a thing. And if he didn't, do you suppose I should sit here and allow him to take such liberties? But I believe it's all your nonsense—and where you got such strange ideas I'm sure I can't tell; not out of Mrs. Trimmer's Sacred History, I'm certain, though you used to read it with me every Sunday afternoon when you were a good little boy, trying to look out of the window all the time, instead of paying proper attention to your books."

During the burst of laughter which followed this speech, and in which Miss Saville, after an ineffectual struggle to repress the inclination, out of respect to Mrs. Coleman, was fain to join, dinner was announced, and Coleman pairing off with the young lady, whilst I gave my arm to the old one, we proceeded to the dining-room.

"Let mirth and music sound the dirge of care,

But ask thou not if happiness be there."

The Lord of the Isles.

"And here she came...

And sang to me the whole Of those three stanzas."

The Talking Oak.

"Yet this is also true, that, long before,

My heart was like a prophet to my heart,

And told me I should love."

Tennyson.

"DON'T you consider Fairlegh to be looking very thin and pale, Miss Saville?" inquired Coleman, when we joined the ladies after dinner, speaking with an air of such genuine solicitude, that any one not intimately acquainted with him must have imagined him in earnest. Miss Saville, who was completely taken in, answered innocently, "Indeed I have thought Mr. Fairlegh much altered since I had the pleasure of meeting him before"; [258] then, glancing at my face with a look of unfeigned interest, which sent the blood bounding rapidly through my veins, she continued: "You have not been ill, I hope?" I was hastening to reply in the negative, and to enlighten her as to the real cause of my pale looks, when Coleman interrupted me by exclaiming:—

"Ah! poor fellow, it is a melancholy affair. In those pale cheeks, that wasted though still graceful form, and the weak, languid, and unhappy, but deeply interesting tout ensemble, you perceive the sad results of—am I at liberty to mention it?—of an unfortunate attachment."

"Upon my word, Freddy, you are too bad," exclaimed I half angrily, though I could scarcely refrain from laughing, for the pathetic expression of his countenance was perfectly irresistible. "Miss Saville, I can assure you—let me beg of you to believe, that there is not a word of truth in what he has stated."

"Wait a moment, you're so dreadfully fast, my dear fellow, you won't allow a man time to finish what he is saying," remonstrated my tormentor—"attachment to his studies I was going to add, only you interrupted me."

"I see I shall have to chastise you before you learn to behave yourself properly," replied I, shaking my fist at him playfully; "remember you taught me how to use the gloves at Dr. Mildman's, and I have not quite forgotten the science even yet."

"Hit a man your own size, you great big monster you," rejoined Coleman, affecting extreme alarm. "Miss Saville, I look to you to protect me from his tyranny; ladies always take the part of the weak and oppressed."

"But they do not interfere to shield evil-doers from the punishment due to their misdemeanours," replied Miss Saville archly.

"There now," grumbled Freddy, "that's always the way; every one turns against me. I'm a victim, though I have not formed an unfortunate attachment for—anything or anybody."

"I should like to see you thoroughly in love for once in your life, Freddy," said I; "it would be as good as a comedy."

"Thank ye," was the rejoinder, "you'd be a pleasant sort of fellow to make a confidant of, I don't think. Here's a man now, who calls himself one's friend, and fancies it would be 'as good as a comedy' to witness the display of our noblest affections, and would have all the tenderest emotions of our nature laid bare, for him to poke fun at—the barbarian!" [259] "I did not understand Mr. Fairlegh's remark to apply to affaires du cour in general, but simply to the effects likely to be produced in your case by such an attack," observed Miss Saville, with a quiet smile.

"A very proper distinction," returned I; "I see that I cannot do better than leave my defence in your hands."

"It is quite clear that you have both entered into a plot against me," rejoined Freddy; "well, never mind, mea virtute me involvo: I wrap myself in a proud consciousness of my own immeasurable superiority, and despise your attacks."

"I have read, that to begin by despising your enemy, is one of the surest methods of losing the battle," replied Miss Saville.

"Oh! if you are going to quote history against me, I yield at once—there is nothing alarms me so much as the sight of a blue-stocking," answered Freddy.

Miss Saville proceeded to defend herself with much vivacity against this charge, and they continued to converse in the same light strain for some time longer; Coleman, as usual, being exceedingly droll and amusing, and the young lady displaying a decided talent for delicate and playful badinage. In order to enter con spirito into this style of conversation, we must either be in the enjoyment of high health and spirits, when our light-heartedness finds a natural vent in gay raillery and sparkling repartee, or we must be suffering a sufficient degree of positive unhappiness to make us feel that a strong effort is necessary to screen our sorrow from the careless gaze of those around us. Now, though Coleman had not been far wrong in describing me as "weak, languid, and unhappy," mine was not a positive, but a negative unhappiness, a gentle sadness, which was rather agreeable than otherwise, and towards which I was by no means disposed to use the slightest violence. I was in the mood to have shed tears with the love-sick Ophelia, or to moralise with the melancholy Jaques, but should have considered Mercutio a man of no feeling, and the clown a "very poor fool" indeed. In this frame of mind, the conversation appeared to me to have assumed such an essentially frivolous turn, that I soon ceased to take any share in it, and, turning over the leaves of a book of prints as an excuse for my silence, endeavoured to abstract my thoughts altogether from the scene around me, and employ them on some subject less dissonant to my present tone of feeling. As is usually the result in such cases, the attempt proved a dead failure, and I soon found [260] myself speculating on the lightness and frivolity of women in general, and of Clara Saville in particular.

"How thoroughly absurd and misplaced," thought I, as her silvery laugh rang harshly on my distempered ear, "were all my conjectures that she was unhappy, and that, in the trustful and earnest expression of those deep blue eyes, I could read the evidence of a secret grief, and a tacit appeal for sympathy to those whom her instinct taught her were worthy of her trust and confidence! Ah! well, I was young and foolish then (it was not quite a year and a half ago), and imagination found an easy dupe in me; one learns to see things in their true light as one grows older, but it is sad how the doing so robs life of all its brightest illusions."

It did not occur to me at that moment that there was a slight injustice in accusing Truth of petty larceny in regard to a bright illusion in the present instance, as the fact (if fact it were) of proving that Miss Saville was happy instead of miserable could scarcely be reckoned among that class of offences.

"Come, Freddy," exclaimed Mrs. Coleman, suddenly waking up to a sense of duty, out of a dangerous little nap in which she had been indulging, and which occasioned me great uneasiness, by reason of the opportunity it afforded her for the display of an alarming suicidal propensity, which threatened to leave Mr. Coleman a disconsolate widower, and Freddy motherless.

As a warning to all somnolent old ladies, it may not be amiss to enter a little more fully into detail. The attack commenced by her sitting bolt upright in her chair, with her eyes so very particularly open, that it seemed as if, in her case, Macbeth or some other wonder-worker had effectually "murdered sleep". By slow degrees, however, her eyelids began to close; she grew less and less "wide awake," and ere long was fast as a church; her next move was to nod complacently to the company in general, as if to demand their attention; she then oscillated gently to and fro for a few seconds to get up the steam, and concluded the performance by suddenly flinging her head back, with an insane jerk, over the rail of the chair, at the imminent risk of breaking her neck, uttering a loud snort of triumph as she did so.

Trusting the reader will pardon, and the humane society award me a medal for this long digression, I resume the thread of my narrative.

"Freddy, my dear, can't you sing us that droll Italian song your cousin Lucy taught you? I'm sure poor Miss Saville must feel quite dull and melancholy."

[261] "Would to Heaven she did!" murmured I to myself. "Who is to play it for me?" asked Coleman. "Well, my love, I'll do my best," replied his mother; "and, if I should make a few mistakes, it will only sound all the funnier, you know."

This being quite unanswerable, the piano was opened, and, after Mrs. Coleman's spectacles had been hunted for in all probable places, and discovered at last in the coal-scuttle, a phenomenon which that good lady accounted for on the score of "John's having flurried her so when he brought in tea"; and when, moreover, she had been with difficulty prevailed on to allow the music-book to remain the right way upwards, the song was commenced.

As Freddy had a good tenor voice, and sang the Italian buffa song with much humour, the performance proved highly successful, although Mrs. Coleman was as good as her word in introducing some original and decidedly "funny" chords into the accompaniment, which would have greatly discomposed the composer, if he had by any chance overheard them.

"I did not know that you were such an accomplished performer, Freddy," observed I; "you are quite an universal genius."

"Oh, the song was capital!" said Miss Saville, "and Mr. Coleman sang it with so much spirit."

"Really," returned Freddy, with a low bow, "you do me proud, as brother Jonathan says; I am actually— that is, positively—"

"My dear Freddy," interrupted Mrs. Coleman, "I wish you would go and fetch Lucy's music; I'm sure Miss Saville can sing some of her songs; it's—let me see—yes, it's either downstairs in the study, or in the boudoir, or in the little room at the top of the house, or, if it isn't, you had better ask Susan about it."

"Perhaps the shortest way will be to consult Susan at once," replied Coleman, as he turned to leave the room.

"I presume you prefer buffa songs to music of a more pathetic character?" inquired I, addressing Miss Saville.

"You judge from my having praised the one we have just heard, I suppose?"

"Yes, and from the lively style of your conversation; I have been envying your high spirits all the evening."

"Indeed!" was the reply; "and why should you envy them?"

"Are they not an indication of happiness, and is not that an enviable possession?" returned I.

"Yes, indeed!" she replied in a low voice, but with such passionate earnestness as quite to startle me. "Is [262] laughing, then, such an infallible indication of happiness?" she continued.

"One usually supposes so," replied I.

To this she made no answer, unless a sigh can be called one, and, turning away, began looking over the pages of a music-book.

"Is there nothing you can recollect to sing, my dear?" asked Mrs. Coleman.

She paused for a moment as if in thought, ere she replied:—

"There is an old air, which I think I could remember; but I do not know whether you will like it. The words," she added, glancing towards me, "refer to the subject on which we have just been speaking."

She then seated herself at the instrument, and, after striking a few simple chords, sang, in a sweet, rich soprano, the following stanzas;—

I

"Behold, how brightly seeming

All nature shows:

In golden sunlight gleaming,

Blushes the rose.

How very happy things must be

That are so bright and fair to see!

Ah, no! in that sweet flower,

A worm there lies;

And lo! within the hour,

It fades—it dies.

II

"Behold, young Beauty's glances

Around she flings;

While as she lightly dances,

Her soft laugh rings:

How very happy they must be,

Who are as young and gay as she!

'Tis not when smiles are brightest,

So old tales say,

The bosom's lord sits lightest—

Ah! well-a-day!

III

"Beneath the greenwood's cover

The maiden steals,

And, as she meets her lover,

Her blush reveals

How very happy all must be

Who love with trustful constancy.

By cruel fortune parted,

She learns too late,

How some die broken-hearted—

Ah! hapless fate!"

[263] The air to which these words were set was a simple, plaintive, old melody, well suited to their expression, and Miss Saville sang with much taste and feeling. When she reached the last four lines of the second verse, her eyes met mine for an instant, with a sad, reproachful glance, as if upbraiding me for having misunderstood her; and there was a touching sweetness in her voice, as she almost whispered the refrain, "Ah! well-a-day!" which seemed to breathe the very soul of melancholy.

"Strange, incomprehensible girl!" thought I, as I gazed with a feeling of interest I could not restrain, upon her beautiful features, which were now marked by an expression of the most touching sadness—"who could believe that she was the same person who, but five minutes since, seemed possessed by the spirit of frolic and merriment, and appeared to have eyes and ears for nothing beyond the jokes and drolleries of Freddy Coleman?"

"That's a very pretty song, my dear," said Mrs. Coleman; "and I'm very much obliged to you for singing it, only it has made me cry so, it has given me quite a cold in my head, I declare;" and, suiting the action to the word, the tender-hearted old lady began to wipe her eyes, and execute sundry other manoeuvres incidental to the malady she had named. At this moment Freddy returned, laden with music-books. Miss Saville immediately fixed upon a lively duet which would suit their voices, and song followed song, till Mrs. Coleman, waking suddenly in a fright, after a tremendous attempt to break her neck, which was very near proving successful, found out that it was past eleven o'clock, and consequently bed-time.

It can scarcely be doubted that my thoughts, as I fell asleep (for, unromantic as it may appear, truth compels me to state that I never slept better in my life), turned upon my unexpected meeting with Clara Saville. The year and a half which had elapsed since the night of the ball had altered her from a beautiful girl into a lovely woman. Without in the slightest degree diminishing its grace and elegance, the outline of her figure had become more rounded, while her features had acquired a depth of expression which was not before observable, and which was the only thing wanting to render them (I had almost said) perfect. In her manner there was also a great alteration; the quiet reserve she had maintained when in the presence of Mr. Vernor, and the calm frankness displayed during our accidental meeting in Barstone [264] Park, had alike given way to a strange excitability, which at times showed itself in the bursts of wild gaiety which had annoyed my fastidious sensitiveness in the earlier part of the evening, at others in the deep impassioned feeling she threw into her singing, though I observed that it was only in such songs as partook of a melancholy and even despairing character that she did so. The result of my meditations was, that the young lady was an interesting enigma, and that I could not employ the next two or three days to better advantage than in "doing a little bit of OEdipus." as Coleman would have termed it, or, in plain English, "finding her out ";—and hereabouts I fell asleep.

"Your riddle is hard to read."

—Tennyson.

'"Are you content?

I am what you behold.

And that's a mystery."

The Two Foscari.

THE post next morning brought a letter from Mr. Vernor to say that, as he found the business on which he was engaged must necessitate his crossing to Boulogne, he feared there was no chance of his being able to return under a week, but that, if it should be inconvenient for Mrs. Coleman to keep Miss Saville so long at Elm Lodge, he should wish her to go back to Barstone, where, if she was in any difficulty, she could easily apply to her late hostess for advice and assistance. On being brought clearly (though I fear the word is scarcely applicable to the good lady's state of mind at any time) to understand the position of affairs, Mrs. Coleman would by no means hear of Miss Saville's departure; but, on the contrary, made her promise to prolong her stay till her guardian should return, which, as Freddy observed, involved the remarkable coincidence that if Mr. Vernor should be drowned in crossing the British Channel, she (his mother) would have put her foot in it. The same post brought Freddy a summons from his father, desiring him, the moment he returned from Bury with the papers, to proceed to town immediately. There was nothing left for him, therefore, but to deposit himself upon the roof of the next coach, blue bag in hand, which he accordingly did, after having spent the intervening time in reviling [265] all lawyers, clients, deeds, settlements, in fact, every individual thing connected with the profession, excepting fees.

"Clara and I are going for a long walk, Mr. Fairlegh, and we shall be glad of your escort, if you have no objection to accompany us, and it is not too far for you," said Mrs. Coleman (who evidently considered me in the last stage of a decline), trotting into the breakfast-room where I was lounging, book in hand, over the fire, wondering what possible pretext I could invent for joining the ladies.

"I shall be only too happy," answered I, "and I think I can contrive to walk as far as you can, Mrs. Coleman." "Oh! I don't know that," was the reply, "I am a capital walker, I assure you. I remember a young man, quite as young as you, and a good deal stouter, who could not walk nearly as far as I can; to be sure," she added as she left the room, "he had a wooden leg, poor fellow!"

I soon received a summons to start with the ladies, whom I found awaiting my arrival on the terrace walk at the back of the house, comfortably wrapped up in shawls and furs, for, although a bright sun was shining, the day was cold and frosty.

"You must allow me to carry that for you," said I, laying violent hands on a large basket, between which and a muff Mrs. Coleman was in vain attempting to effect an amicable arrangement.

"Oh, dear! I'm sure you'll never be able to carry it—it's so dreadfully heavy," was the reply.

"Nous verrons," answered I, swinging it on my forefinger, in order to demonstrate its lightness.

"Take care—you mustn't do so!" exclaimed Mrs. Coleman in a tone of extreme alarm; "you'll upset all my beautiful senna tea, and it will get amongst the slices of Christmas plum-pudding, and the flannel that I'm going to take for poor Mrs. Muddles's children to eat; do you know Mrs. Muddles, Clara, my dear?"

Miss Saville replied in the negative, and Mrs. Coleman continued:—

"Ah! poor thing! she's a very hard-working, respectable, excellent young woman; she has been married three years, and has got six children—no! let me see—it's six years, and three children—that's it—though I can never remember whether it's most pigs or children she has—four pigs, did I say?—but it doesn't much signify, for the youngest is a boy and will soon be fat enough to kill—the pig I mean, and they're all very dirty, and have never [266] been taught to read, because she takes in washing, and has put a great deal too much starch in my night-cap this week—only her husband drinks—so I mustn't say much about it, poor thing, for we all have our failings, you know."

With suchlike rambling discourse did worthy Mrs. Coleman beguile the way, until at length, after a walk of some two miles and a half, we arrived at the cottage of that much-enduring laundress, the highly respectable Mrs. Muddles, where, in due form, we were introduced to the mixed race of children and pigs, between which heads clearer than that of Mrs. Coleman might have been at a loss to distinguish; for if the pigs did not exactly resemble children, the children most assuredly looked like pigs. Here we seemed likely to remain for some time, as there was much business to be transacted by the two matrons. First, Mrs. Coleman's basket was unpacked, during which process that lady delivered a long harangue, setting forth the rival merits of plum-pudding and black draught, and ingeniously establishing a connexion between them, which has rendered the former nearly as distasteful to me as the latter ever since. Thence glancing slightly at the overstarched night-cap, and delicately referring to the anti-teetotal propensities of the laundress's sposo, she contrived so thoroughly to confuse and interlace the various topics of her discourse, as to render it an open question, whether the male Muddles had not got tipsy on black draught, in consequence of the plum-pudding having overstarched the night-cap; moreover, she distinctly called the latter article "poor fellow!" twice. In reply to this, Mrs. Muddles, the skin of whose hands was crimped up into patterns like sea-weed, from the amphibious nature of her employment, and whose general appearance was, from the same cause, moist and spongy, expressed much gratitude for the contents of the basket, made a pathetic apology to the night-cap, tried to ignore the imbibing propensity of her better half; but, when pressed home upon the point, declared that when he was not engaged in the Circe-like operation of "making a beast of hisself," he was one of the most virtuousest of men; and finally wound up by a minute medical detail of Johnny's chilblain, accompanied by a slight retrospective sketch of Mary Anne's departed hooping-cough. How much longer the conversation might have continued, it is impossible to say, for it was evident that neither of the speakers had by any means exhausted her budget, had not Johnny, the unfortunate proprietor of the chilblain above alluded to, seen fit to precipitate himself, head-foremost, into a washing-tub [267] of nearly scalding water, whence his mamma, with great presence of mind and much professional dexterity, extricated him, wrung him out, and set him on the mangle to dry, where he remained sobbing, from a vague sense of humid misery, till a more convenient season.

This little incident reminding Mrs. Coleman that the boiled beef, preparing for our luncheon and the servants' dinner, would inevitably be overdone, induced her to take a hurried farewell of Mrs. Muddles, though she paused at the threshold to offer a parting suggestion as to the advisability, moral and physical, of dividing the wretched Johnny's share of plum-pudding between his brothers and sisters, and administering a double portion of black draught by way of compensation, an arrangement which elicited from that much-wronged child a howl of mingled horror and defiance.

We had proceeded about a mile on our return, when Mrs. Coleman, who was a step or two in advance, trod on a slide some boys had made, and would have fallen had I not thrown my arm round her just in time to prevent it.

"My dear madam," exclaimed I, "you were as nearly as possible down; I hope you have not hurt yourself."

"No, my dear—I mean—Mr. Fairlegh; no! I hope I have not, except my ankle. I gave that a twist somehow, and it hurts me dreadfully; but I daresay I shall be able to go on in a minute."

The good lady's hopes, however, were not destined in this instance to be fulfilled, for, on attempting to proceed, the pain increased to such an extent, that she was forced, after limping a few steps, to seat herself on a stone by the wayside, and it became evident that she must have sprained her ankle severely, and would be utterly unable to walk home. In this dilemma it was not easy to discover what was the best thing to do—no vehicle could be procured nearer than Hillingford, from which place we were at least two miles distant, and I by no means approved of leaving my companions in their present helpless state during the space of time which must necessarily elapse ere I could go and return. Mrs. Coleman, who, although suffering from considerable pain, bore it with the greatest equanimity and good nature, seeming to think much more of the inconvenience she was likely to occasion us, than of her own discomforts, had just hit upon some brilliant but totally impracticable project, when our ears were gladdened by the sound of wheels, and in another moment a little pony-chaise, drawn by a [268] fat, comfortable-looking pony, came in sight, proceeding in the direction of Hillingford. As soon as the driver, a stout, rosy-faced gentleman, who proved to be the family apothecary, perceived our party, he pulled up, and, when he became aware of what had occurred, put an end to our difficulties by offering Mrs. Coleman the unoccupied seat in his chaise.

"Sorry I can't accommodate you also, Miss Saville," he continued, raising his hat; "but you see it's rather close packing as it is. If I were but a little more like the medical practitioner who administered a sleeping draught to Master Romeo now, we might contrive to carry three."

"I really prefer walking such a cold day as this, thank you, Mr. Pillaway," answered Miss Saville.

"Mind you take proper care of poor Clara, Mr. Fairlegh," said Mrs. Coleman, "and don't let her sprain her ankle, or do anything foolish, and don't you stay out too long yourself and catch cold, or I don't know what Mrs. Fairlegh will say, and your pretty sister, too—what a fat pony, Mr. Pillaway; you don't give him much physic, I should think—good-bye, my dears, good-bye—remember the boiled beef."

As she spoke, the fat pony, admonished by the whip, described a circle with his tail, frisked with the agility of a playful elephant, and then set off at a better pace than from his adipose appearance I had deemed him capable of doing.

"With all her oddity, what an unselfish, kind-hearted, excellent little person Mrs. Coleman is!" observed I, as the pony-chaise disappeared at an angle of the road.

"Oh! I think her charming," replied my companion warmly, "she is so very good-natured."

"She is something beyond that," returned I; "mere good-nature is a quality I rate very low: a person may be good-natured, yet thoroughly selfish, for nine times out of ten it is easier and more agreeable to say 'yes' than 'no'; but there is such an entire forgetfulness of self, apparent in all Mrs. Coleman's attempts to make those around her happy and comfortable, that, despite her eccentricities, I am beginning to conceive quite a respect for the little woman."

"You are a close observer of character it seems, Mr. Fairlegh," remarked my companion.

"I scarcely see how any thinking person can avoid being so," returned I; "there is no study that appears to me to possess a more deep and varied interest."

"You make mistakes, though, sometimes," replied [269] Miss Saville, glancing quickly at me with her beautiful eyes.

"You refer to my hasty judgment of last night," said I, colouring slightly. "The mournful words of your song led me to conclude that, in one instance, high spirits might not be a sure indication of a light heart; and yet I would fain hope," added I in a half-questioning tone, "that you merely sought to inculcate a general principle."

"Is not that a very unusual species of heath to find growing in this country?" was the rejoinder.

"Really, I am no botanist," returned I, rather crossly, for I felt that I had received a rebuff, and was not at all sure that I might not have deserved it.

"Nay, but I will have you attend; you did not even look towards the place where it is growing," replied Miss Saville, with a half-imperious, half-imploring glance, which it was impossible to resist.

"Is that the plant you mean?" asked I, pointing to a tuft of heath on the top of a steep bank by the roadside.

On receiving a reply in the affirmative, I continued: "Then I will render you all the assistance in my power, by enabling you to judge for yourself ". So saying, I scrambled up the bank at the imminent risk of my neck; and after bursting the button-holes of my straps, and tearing my coat in two places with a bramble, I succeeded in gathering the heath.

Elated by my success, and feeling every nerve braced and invigorated by the frosty air, I bounded down the slope with such velocity, that, on reaching the bottom, I was unable to check my speed, and only avoided running against Miss Saville, by nearly throwing myself down backwards.

"I beg your pardon!" exclaimed I; "I hope I have not alarmed you by my abominable awkwardness; but really the bank was so steep, that it was impossible to stop sooner."

"Nay, it is I who ought to apologise for having led you to undertake such a dangerous expedition," replied she, taking the heath which I had gathered, with a smile which quite repaid me for my exertions.

"I do not know what could have possessed me to run down the bank in that insane manner," returned I; "I suppose it is this fine frosty morning which makes one feel so light and happy."

"Happy!" repeated my companion incredulously, and in a half-absent manner, as though she were rather thinking aloud than addressing me.

[270] "Yes," replied I, surprised; "why should I not feel so?"

"Is any one happy?" was the rejoinder.

"Very many people, I hope," said I; "you do not doubt it, surely."

"I well might," she answered with a sigh.

"On such a beautiful day as this, with the bright clear sky above us, and the hoar-frost sparkling like diamonds in the glorious sunshine, how can one avoid feeling happy?" asked I.

"It is very beautiful," she replied, after gazing around for a moment; "and yet can you not imagine a state of mind in which this fair scene, with all its varied charms, may impress one with a feeling of bitterness rather than of pleasure, by the contrast it affords to the darkness and weariness of soul within? Place some famine-stricken wretch beneath the roof of a gilded palace, think you the sight of its magnificence would give him any sensation of pleasure? Would it not rather, by increasing the sense of his own misery, add to his agony of spirit?"

"I can conceive such a case possible," replied I; "but you would make us out to be all famine-stricken wretches at this rate: you cannot surely imagine that every one is unhappy?"

"There are, no doubt, different degrees of unhappiness," returned Miss Saville; "yet I can hardly conceive any position in life so free from cares, as to be pronounced positively happy; but I know my ideas on this subject are peculiar, and I am by no means desirous of making a convert of you, Mr. Fairlegh; the world will do that soon enough, I fear," she added with a sigh.

"I cannot believe it," replied I warmly. "True, at times we must all feel sorrow; it is one of the conditions of our mortal lot, and we must bear it with what resignation we may, knowing that, if we but make a fitting use of it, it is certain to work for our highest good; but if you would have me look upon this world as a vale of tears, forgetting all its glorious opportunities for raising our fallen nature to something so bright and noble, as to be even here but little lower than the angels, you must pardon me if I never can agree with you."

There was a moment's pause, when my companion resumed.

"You talk of opportunities of doing good, as being likely to increase our stock of happiness; and, no doubt, you are right; but imagine a situation, in which you are unable to take advantage of these opportunities when [271] they arise—in which you are not a free agent, your will fettered and controlled on every point, so that you are alike powerless to perform the good that you desire, and to avoid the evil you both hate and fear—could you be happy in such a situation, think you?"

"You describe a case which is, or ought to be, impossible," replied I; "when I say ought to be, I mean that in these days, I hope and believe, it is impossible for any one to be forced to do wrong, unless, from a natural weakness and facility of disposition, and from a want of moral courage, their resistance is so feeble, that those who seek to compel them to evil are induced to redouble their efforts, when a little firmness and decision clearly shown, and steadily adhered to, would have produced a very different result."

"Oh that I could think so!" exclaimed Miss Saville ardently: she paused for a minute, as if in thought, and then resumed in a low mournful voice, "But you do not know—you cannot tell; besides, it is useless to struggle against destiny: there are people fated from childhood to grief and misfortune—alone in this cold world"—she paused, then continued abruptly, "you have a sister?"

"Yes," replied I; "I have as good a little sister as ever man was fortunate enough to possess—how glad I should be to introduce her to you!"

"And you love each other?"

"Indeed we do, truly and sincerely."

"And you are a man, one of the lords of the creation," she continued, with a slight degree of sarcasm in her tone. "Well, Mr. Fairlegh, I can believe that you may be happy sometimes."

"And what ami to conjecture about you?" inquired I, fixing my eyes upon her expressive features.

"What you please," returned she, turning away with a very becoming blush—"or rather," she added, "do not waste your time in forming any conjectures whatever on such an uninteresting subject."

"I am more easily interested than you imagine," replied I, with a smile; "besides, you know I am fond of studying character."

"The riddle is not worth reading," answered Miss Saville.

"Nevertheless, I shall not be contented till I have found it out; I shall guess it before long, depend upon it," returned I.

An incredulous shake of the head was her only reply, and we continued conversing on indifferent subjects till we reached Elm Lodge.[272]

"Good company's a chess-board—there are kings,

Queens, bishops, knights, rooks, pawns.

The world's a game."

Byron.

"My soul hath felt a secret weight,

A warning of approaching fate."

Rokeby.

"Oh! lady, weep no more; lest I give cause

To be suspected of more tenderness

Than doth become a man."

Shakspeare.

THE next few days passed like a happy dream. Our little party remained the same, no tidings being heard of any of the absentees, save a note from Freddy, saying how much he was annoyed at being detained in town, and begging me to await his return at Elm Lodge, or he would never forgive me. Mrs. Coleman's sprain, though not very severe, was yet sufficient to confine her to her own room till after breakfast, and to a sofa in the boudoir during the rest of the day; and, as a necessary consequence, Miss Saville and I were chiefly dependent on each other for society and amusement. We walked together, read Italian (Petrarch too, of all the authors we could have chosen, to beguile us with his picturesque and glowing love conceits), played chess, and, in short, tried in turn the usual expedients for killing time in a country-house, and found them all very "pretty pastimes" indeed. As the young lady's shyness wore off, and by degrees she allowed the various excellent qualities of her head and heart to appear, I recalled Lucy Markham's assertion, that "she was as good and amiable as she was pretty," and acknowledged that she had only done her justice. Still, although her manner was generally lively and animated, and at times even gay, I could perceive that her mind was not at ease; and whenever she was silent, and her features were in repose, they were marked by an expression of hopeless dejection which it grieved me to behold. If at such moments she perceived any one was observing her, she would rouse herself with a sudden start, and join in the conversation with a degree of wild vehemence and strange, unnatural gaiety, which to me had in it something shocking. Latterly, however, as we became better acquainted, and felt more at ease in [273] each other's society, these wild bursts of spirits grew less frequent, or altogether disappeared, and she would meet my glance with a calm melancholy smile, which seemed to say, "I am not afraid to trust you with the knowledge that I am unhappy—you will not betray me". Yet, though she seemed to find pleasure in discussing subjects which afforded opportunity for expressing the morbid and desponding views she held of life, she never allowed the conversation to take a personal turn, always skilfully avoiding the possibility of her words being applied to her own case: any attempt to do so invariably rendering her silent, or eliciting from her some gay piquant remark, which served her purpose still better.

And how were my feelings getting on all this time? Was I falling in love with this wayward, incomprehensible, but deeply interesting girl, into whose constant society circumstances had, as it were, forced me? Reader, this was a question which I most carefully abstained from asking myself. I knew that I was exceedingly happy; and, as I wished to continue so, I steadily forbore to analyse the ingredients of this happiness too closely, perhaps from a secret consciousness, that, were I to do so, I might discover certain awkward truths, which would prove it to be my duty to tear myself away from the scene of fascination ere it was too late. So I told myself that I was bound by my promise to Coleman to remain at Elm Lodge till my mother and sister should return home, or, at all events, till he himself came back: this being the case, I was compelled by all the rules of good-breeding to be civil and attentive to Miss Saville (yes, civil and attentive—I repeated the words over two or three times; they were nice, quiet, cool sort of words, and suited the view I was anxious to take of the case particularly well). Besides, I might be of some use to her, poor girl, by combating her strange, melancholy, half-fatalist opinions; at all events, it was my duty to try, decidedly my duty (I said that also several times); and, as to my feeling such a deep interest about her, and thinking of her continually, why there was nothing else to think about at Elm Lodge—so that was easily accounted for. All this, and a good deal more of the same nature, did I tell myself; and, if I did not implicitly believe it, I was much too polite to think of giving myself the lie, and so I continued walking, talking, reading Petrarch, and playing chess with Miss Saville all day, and dreaming of her all night, and being very happy indeed.

[274] Oh! it's a dangerous game, by the way, that game of chess, with its gallant young knights, clever fellows, up to all sorts of deep moves, who are perpetually laying siege to queens, keeping them in check, threatening them with the bishop, and, with his assistance, mating at last; and much too nearly does it resemble the game of life to be played safely with a pair of bright eyes talking to you from the other side of the board, and two coral lips—mute, indeed, but in their very silence discoursing such "sweet music" to your heart, that the silly thing, dancing with delight, seems as if it meant to leap out of your breast; and it is not mere seeming either—for hearts have been altogether lost in this way before now. Oh! it's a dangerous game, that game of chess. But to return to my tale.

About a week after the expedition to Mrs. Muddles's had taken place, Freddy and his father returned, just in time for dinner. As I was dressing for that meal Coleman came into my room, anxious to learn "how the young lady had conducted herself" during his absence; whether I had taken any unfair advantage, or acted honourably, and with a due regard to his interest, with sundry other jocose queries, all of which appeared to me exceedingly impertinent, and particularly disagreeable, and inspired me with a strong inclination to take him by the shoulders and march him out of the room; instead, however, of doing so, I endeavoured to look amiable, and answer his inquiries in the same light tone in which they were made, and I so far succeeded as to render the amount of information he obtained exceedingly minute. The dinner passed off heavily; Miss Saville was unusually silent, and all Freddy's sallies failed to draw her out. Mr. Coleman was very pompous, and so distressingly polite, that everything like sociability was out of the question. When the ladies left us, matters did not improve; Freddy, finding the atmosphere ungenial to jokes, devoted himself to cracking walnuts by original methods which invariably failed, and attempting to torture into impossible shapes oranges which, when finished, were much too sour for any one to eat; while his father, after having solemnly, and at separate intervals, begged me to partake of every article of the dessert twice over, commenced an harangue, in which he set forth the extreme caution and reserve he considered it right and advisable for young gentlemen to exercise in their intercourse with young ladies, towards whom he declared they should maintain a staid deportment of dignified [275] courtesy, tempered by distant but respectful attentions. This, repeated with variations, lasted us till the tea was announced, and we returned to the drawing-room. Here Freddy made a desperate and final struggle to remove the wet blanket which appeared to have extinguished the life and spirit of the party, but in vain; it had evidently set in for a dull evening, and the clouds were not to be dispelled by any efforts of his;—nothing, therefore, remained for him but to tease the cat, and worry and confuse his mother, to which occupations he applied himself with a degree of diligence worthy a better object. During a fearful commotion consequent upon the discovery of the cat's nose in the cream-jug, into the commission of which delinquency Freddy had contrived to inveigle that amiable quadruped by a series of treacherous caresses, I could not help remarking to Miss Saville (next to whom I happened to be seated) the contrast between this evening and those which we had lately spent together.

"Ah! yes," she replied, in a half-absent manner, "I knew they were too happy to last;" then seeing, from the flush of joy which I felt rise to my brow, though I would have given worlds to repress it, that I had put a wrong construction on her words, or, as my heart would fain have me believe, that she had unconsciously admitted more than she intended, she added hastily, "What I mean to say is, that the perfect freedom from restraint, and the entire liberty to—to follow one's own pursuits, are pleasures to which I am so little accustomed, that I have enjoyed them more than I was perhaps aware of while they lasted".

"You are out of spirits this evening. I hope nothing has occurred to annoy you?" inquired I.

"Do you believe in presentiments?" was the rejoinder.

"I cannot say I do," returned I; "I take them to be little else than the creations of our own morbid fancies, and attribute them in great measure to physical causes."

"But why do they come true, then?" she inquired. "I must answer your question by another," I replied, "and ask whether, except now and then by accident, they do come true?"

"I think so," returned Miss Saville, "at least I can only judge as one usually does, more or less, in every case, by one's own experience,—my presentiments always appear to come true; would it were not so! for they are generally of a gloomy nature."

"Even yet," replied I, "I doubt whether you do not [276] unconsciously deceive yourself, and I think I can tell you the reason; you remember the times when your presentiments have come to pass, because you considered such coincidences remarkable, and they made a strong impression on your mind, while you forget the innumerable gloomy forebodings which have never been fulfilled, the accomplishment being the thing which fixes itself on your memory—is not this the case?"

"It may be so," she answered, "and yet I know not—even now there is a weight here," and she pressed her hand to her brow as she spoke, "a vague, dull feeling of dread, a sensation of coming evil, which tells me some misfortune is at hand, some crisis of my fate approaching. I daresay you consider all this very silly and romantic, Mr. Fairlegh; but if you knew how everything I have most feared, most sought to avoid, has invariably been forced upon me, you would make allowance for me—you would pity me."

What answer I should have made to this appeal, had not Fate interposed in the person of old Mr. Coleman (who seated himself on the other side of Miss Saville, and began talking about the state of the roads), it is impossible to say. As it was my only reply was by a glance, which, if it failed to convince her that I pitied her with a depth and intensity which approached alarmingly near the kindred emotion, love, must have been singularly inexpressive. And the evening came to an end, as all evenings, however long, are sure to do at last; and in due course I went to bed, but not to sleep, for Clara Saville and her forebodings ran riot in my brain, and effectually banished the "soft restorer," till such time as that early egotist the cock began singing his own praises to his numerous wives, when I fell into a doze, with a strong idea that I had got a presentiment myself, though of what nature, or when the event (if event it was) was likely to "come off," I had not the most distant notion.

The post-bag arrived while we were at breakfast the next morning; and it so happened that I was the only one of the party for whom it did not contain a letter. Having nothing, therefore, to occupy my attention, and being seated exactly opposite Clara Saville, I could scarcely fail to observe the effect produced by one which Mr. Coleman had handed to her. When her eye first fell on the writing she gave a slight start, and a flush (I could not decide whether of pleasure or anger) mounted to her brow. As she perused the contents she grew deadly pale, and I feared she was about to faint: recovering herself, [277] however, by a strong effort, she read steadily to the end, quietly refolded the letter, and, placing it in a pocket in her dress, apparently resumed her breakfast—I say apparently, for I noticed that, although she busied herself with what was on her plate, it remained untasted, and she took the earliest opportunity, as soon as the meal was concluded, of leaving the room.

"I'm afraid I must ask you to excuse me till after lunch, old fellow," said Coleman, "you see we're so dreadfully busy just now with this confounded suit I went down to Bury about—'Bowler versus Stumps'; but if you can amuse yourself till two o'clock we'll go and have a jolly good walk to shake up an appetite for dinner."

"The very thing," replied I; "I have a letter to Harry Oaklands which has been on the stocks for the last four days, and which I particularly wish to finish, and then I'm your man, for a ten-mile trot if you like it."

"So be it, then," said Freddy, leaving the room as he spoke.

As soon as he was gone, instead of fetching my half-written epistle I flung myself into an arm-chair, and devoted myself to the profitable employment of conjecturing the possible cause of Clara Saville's strange agitation on receiving that letter. Who could it be from?—perhaps her guardian;—but if so, why should she have given a start of surprise?—nothing could have been more natural or probable than that he should write and say when she might expect him home—she could not have felt surprise at the sight of his handwriting—but if not from him, from whom could it come? She had told me that she had no near relations, no intimate friend. A lover perchance—well, and if it were so, what was that to me?—nothing—oh yes! decidedly nothing—a favoured lover of course, else why the emotion?—was this also nothing?—yes, I said it was, and I tried to think so too: yet, viewing the matter so philosophically, it was rather inconsistent to spring from my seat as if an adder had stung me, and begin striding up and down the room as though I were walking for a wager. In the course of my rapid promenade, my coat-tail brushed against and nearly knocked down an inkstand, to which incident I was indebted for the recollection of my unfinished letter to Oaklands, and, my own thoughts being at that moment no over-pleasant companions, I was glad of any excuse to get rid of them. On looking about for my writing-case, however, I remembered that, when last I made use of it, we were sitting in the boudoir, and that there it had [278] probably remained ever since; accordingly, without further waste of time, I ran upstairs to look for it.

As good Mrs. Coleman (although she most indignantly repelled the accusation) was sometimes accustomed to indulge her propensity for napping even in a morning, I opened the door of the boudoir, and closed it again after me as noiselessly as possible. My precautions, however, did not seem to have been necessary, for at first sight the room appeared untenanted; but as I turned to look for my writing-case a stifled sob met my ear, and a closer inspection enabled me to perceive the form of Clara Saville, with her face buried in the cushions, half-sitting, half-reclining on the sofa, while so silently had I effected my entrance that as yet she was not aware of my approach. My first impulse was to withdraw and leave her undisturbed, but unluckily a slight noise which I made in endeavouring to do so attracted her attention, and she started up in alarm, regarding me with a wild, half-frightened gaze, as if she scarcely recognised me.

"I beg your pardon," I began hastily, "I am afraid I have disturbed you—I came to fetch—that is to look for—my—" and here I stopped short, for to my surprise and consternation Miss Saville, after making a strong but ineffectual effort to regain her composure, sank back upon the sofa, and, covering her face with her hands, burst into a violent flood of tears. I can scarcely conceive a situation more painful, or in which it would be more difficult to know how to act, than the one in which I now found myself. The sight of a woman's tears must always produce a powerful effect upon a man of any feeling, leading him to wish to comfort and assist her to the utmost of his ability; but, if the fair weeper be one in whose welfare you take the deepest interest, and yet with whom you are not on terms of sufficient intimacy to entitle you to offer the consolation your heart would dictate, the position becomes doubly embarrassing. For my part, so overcome was I by a perfect chaos of emotions, that I remained for some moments like one thunder-stricken, while she continued to sob as though her heart were breaking. At length I could stand it no longer, and scarcely knowing what I was going to say or do, I placed myself on the sofa beside her, and taking one of her hands, which now hung listlessly down, in my own, I exclaimed:—

"Miss Saville—Clara—dear Clara! I cannot bear to see you so unhappy, it makes me miserable to look at you—tell me, what can I do to help you—to comfort you—something must be possible—you have no brother—let [279] me be one to you—tell me why you are so wretched—and oh! do not cry so bitterly!"

When I first addressed her she started slightly, and attempted to withdraw her hand, but as I proceeded she allowed it to remain quietly in mine, and though she still continued to weep, her tears fell more softly, and she no longer sobbed in such a distressing manner. Glad to find that I had in some measure succeeded in calming her, I renewed my attempts at consolation, and again implored her to tell me the cause of her unhappiness. Still for some moments she was unable to speak, but at length making an effort to recover herself she withdrew her hand, and stroking back her glossy hair, which had fallen over her forehead, said:—

"This is very weak—very foolish. I do not often give way in this manner, but it came upon me so suddenly—so unexpectedly; and now, Mr. Fairlegh, pray leave me; I shall ever feel grateful to you for your sympathy, for your offers of assistance, and for all the trouble you have kindly taken about such a strange, wayward girl, as I am sure you must consider me," she added, with a faint smile.

"So you will not allow me to be of use to you," returned I sorrowfully, "you do not think me worthy of your confidence."

"Indeed it is not so," she replied earnestly; "there is no one of whose judgment I think more highly; no one of whose assistance I would more gladly avail myself; on whose honour I would more willingly rely; but it is utterly impossible to help me. Indeed," she added, seeing me still look incredulous, "I am telling you what I believe to be the exact and simple truth."

"Will you promise me that, if at any time you should find that I could be of use to you, you will apply to me as you would to a brother, trusting me sufficiently to believe that I shall not act hastily, or in any way which could in the slightest degree compromise or annoy you? Will you promise me this?"

"I will," she replied, raising her eyes to my face for an instant with that sweet, trustful expression which I had before noticed, "though I suppose such prudent people as Mr. Coleman," she added with a slight smile, "would consider me to blame for so doing; and were I like other girls—had I a mother's affection to watch over me—a father's care to shield me, they might be right; but situated as I am, having none to care for me—nothing to rely on save my own weak heart and unassisted judgment—while those who should guide and protect me [280] appear only too ready to avail themselves of my helplessness and inexperience—I cannot afford to lose so true a friend, or believe it to be my duty to reject your disinterested kindness."

A pause ensued, during which I arrived at two conclusions—first, that my kindness was not altogether so disinterested as she imagined; and secondly, that if I sat where I was much longer, and she continued to talk about there being nobody who cared for her, I should inevitably feel myself called upon to undeceive her, and, as a necessary consequence, implore her to accept my heart and share my patrimony—the latter, deducting my sister's allowance and my mother's jointure, amounting to the imposing sum of £90 14s. 6d. per annum, which, although sufficient to furnish a bachelor with bread and cheese and broad-cloth, was not exactly calculated to afford an income for "persons about to marry". Accordingly, putting a strong force upon my inclinations, and by a desperate effort screwing my virtue to the sticking point, I made a pretty speech, clenching, and thanking her for her promise of applying to me to help her out of the first hopelessly inextricable dilemma in which she might find herself involved, and rose with the full intention of leaving the room.

"Think'st thou there's virtue in constrained vows,

Half utter'd, soulless, falter'd forth in fear?

And if there is, then truth and grace are nought."

Sheridan Knowles.

"For The contract you pretend with that base wretch,

It is no contract—none."

Shakspeare.

"Who hath not felt that breath in the air,

A perfume and freshness strange and rare,

A warmth in the light, and a bliss everywhere,

When young hearts yearn together?

All sweets below, and all sunny above,

Oh! there's nothing in life like making Love,

Save making hay in fine weather!

Hood.

UPON what trifles do the most important events of our lives turn! Had I quitted the room according to my intention, I should not have had an opportunity of seeing Miss Saville alone again (as she returned to Barstone [281] that afternoon), in which case she would probably have forgotten, or felt afraid to avail herself of my promised assistance, all communication between us would have ceased, and the deep interest I felt in her, having nothing wherewith to sustain itself, would, as years passed by, have died a natural death.

Good resolutions are, however, proverbially fragile, and, in nine cases out of ten, appear made, like children's toys, only to be broken. Certain it is, that in the present instance mine were rendered of none avail, and, for any good effect that they produced, might as well never have been formed.

As I got up to leave the room Miss Saville rose likewise, and in doing so accidentally dropped a, or rather the, letter, which I picked up, and was about to return to her, when suddenly my eye fell upon the direction, and I started as I recognised the writing—a second glance served to convince me that I had not been mistaken, for the hand was a very peculiar one; and, turning to my astonished companion, I exclaimed, "Clara, as you would avoid a life of misery, tell me by what right this man dares to address you!"

"What! do you know him, then?" she inquired anxiously.

"If he be the man I mean," was my answer, "I know him but too well, and he is the only human being I both dislike and despise. Was not that letter written by Richard Cumberland?"

"Yes, that is his hateful name," she replied, shuddering while she spoke, as at the aspect of some loathsome thing; then, suddenly changing her tone to one of the most passionate entreaty, she clasped her hands, and advancing a step towards me, exclaimed:—

"Oh! Mr. Fairlegh, only save me from him, and I will bless you, will pray for you!" and completely overcome by her emotion, she sank backwards, and would have fallen had not I prevented it.

There is a peculiar state of feeling which a man sometimes experiences when he has bravely resisted some hydra-headed temptation to do anything "pleasant but wrong," yet which circumstances appear determined to force upon him: he struggles against it boldly at first; but, as each victory serves only to lessen his own strength, while that of the enemy continues unimpaired, he begins to tell himself that it is useless to contend longer—that the monster is too strong for him, and he yields at last, from a mixed feeling of fatalism and irritation—a sort of [282] "have-it-your-own-way-then" frame of mind, which seeks to relieve itself from all responsibility by throwing the burden on things in general—the weakness of human nature—the force of circumstances—or any other indefinite and conventional scapegoat, which may serve his purpose of self-exculpation.

In much such a condition did I now find myself; I felt that I was regularly conquered—completely taken by storm—and that nothing was left for me but to yield to my destiny with the best grace I could. I therefore seated myself by Miss Saville on the sofa, and whispered, "You must promise me one thing more, Clara, dearest—say that you will love me—give me but that right to watch over you—to protect you, and believe me neither Cumberland, nor any other villain, shall dare for the future to molest you".

As she made no answer, but remained with her eyes fixed on the ground, while the tears stole slowly down her cheeks, I continued—"You own that you are unhappy—that you have none to love you—none on whom you can rely;—do not then reject the tender, the devoted affection of one who would live but to protect you from the slightest breath of sorrow—would gladly die, if, by so doing, he could secure your happiness".

"Oh! hush, hush!" she replied, starting, as if for the first time aware of the tenor of my words; "you know not what you ask; or even you, kind, noble, generous as you are, would not seek to link your fate with one so utterly wretched, so marked out for misfortune as myself. Stay," she continued, seeing that I was about to speak, "hear me out. Richard Cumberland, the man whom you despise, and whom I hate only less than I fear, that man have I promised to marry, and, ere this, he is on his road hither to claim the fulfilment of the engagement."

"Promised to marry Cumberland!" repeated I mechanically, "a low, dissipated swindler—a common cheat, for I can call him nothing better; oh, it's impossible!—why, Mr. Vernor, your guardian, would never permit it."